Quick

River

Primer

By Sarah Taylor, co-founder and board member of Braided River Campaign. Share your comments and questions with Sarah at sarahsojourner@mac.com.

Quick Lesson #1: The North Reach

What is the North Reach of the Willamette River?

The North Reach refers to the last nine miles of the Willamette River from the Broadway Bridge to where the Willamette River meets the Columbia River at Kelly Point Park. Portland divided its part of the Willamette River into three sections; the south, central and north reach. These terms were created as part of the state mandated Greenway Plan for every area that borders the Willamette River.

What is the Lower Willamette River?

The area from Willamette Falls to the confluence with the Columbia River is known as the Lower Willamette. This part of the river is tidal and flows through Portland. The tidal changes can cause the river to change its depth and even change the direction it flows. A very low tide can cause the river to change direction and flow south.

What Portland city council districts are impacted by decisions in the North Reach?

Every city council district in Portland borders the Willamette or Columbia Rivers, the Columbia Slough, or creeks that are tributaries of the Willamette River. District 2 and 4 are directly part of the North Reach.

Quick Lesson #2: Portland’s North Peninsula

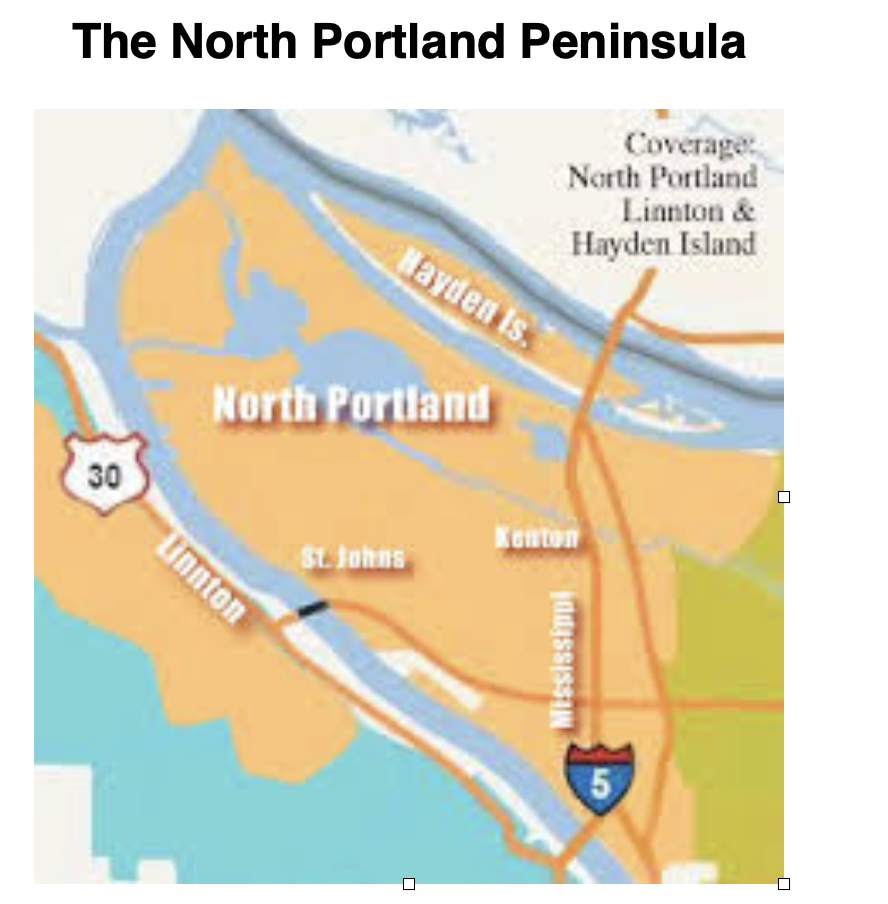

Where is Portland’s North Peninsula?

North Portland is composed of two rivers, the Willamette and the Columbia, that meet to create a peninsula. The land between the two rivers and the mountains, to the west, create a unique landscape that best describes the Northern reaches of our city.

Why is Portland’s North Peninsula a special place ?

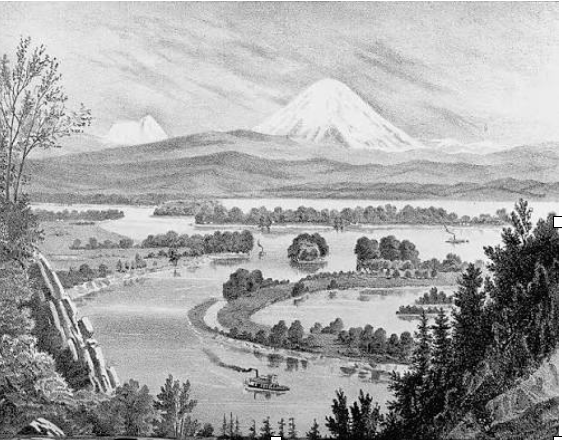

The peninsula was traditionally a place abundantly interwoven with lakes, streams, sloughs, and wetlands; rich in wildlife, fish and forests. It served as a place of villages; a transportation corridor and meeting place for tribes along the Columbia and Willamette Rivers since time immemorial.

Quick Lesson #3: How was the North Reach and Peninsula formed?

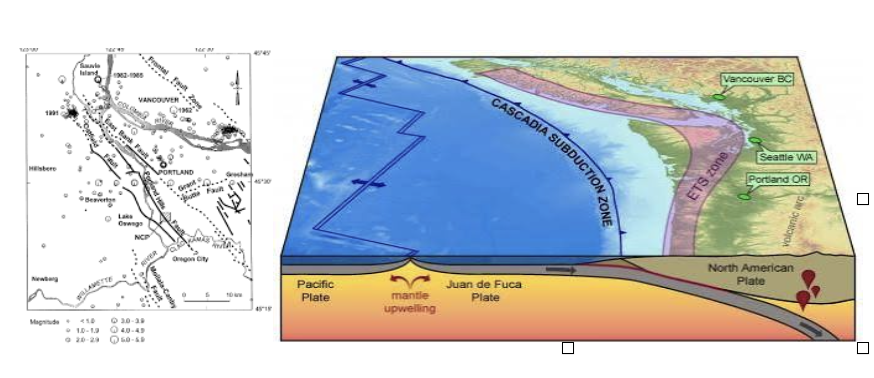

The Willamette River and the surrounding lands were formed by millions of years of volcanic activity accompanied by shifting plate tectonics, ice ages and melting glaciers.

About 15,000 years ago, the Missoula Floods swept through a valley creating a vast braided river system which we now know as the Willamette River. Layers of sediment and rock were deposited on the banks. This created the fertile soils that make the Willamette Valley a welcoming place for plants and farming. It also means that the land we build on is rarely bedrock.

The same systems of shifting plate tectonics continue to exist and create fault lines beneath the city. The larger Cascadia Subduction Zone (CSZ) Fault Line runs along the west coast of North America and is predicted to lead to large earthquakes in the future. Soil along the Willamette River will “Liquify” and slip into the river. Geologists predict that the structures built on liquifiable soil will slip into the river including the liquid fuel tanks.

Quick Lesson #4: The Willamette River was a Braided River

Rivers can be described by the shape of their channel. Examples include meandering, braided, straight and anastomosing. Our city’s river was a braided river.

A Braided River has islands (Like Swan Island, Ross Island and Sauvie’s Island) and many off channel lakes and streams. (Like the former Guilds Lake and Smith and Bybee Lakes)

A braided river weaves around islands and streams. It floods and the North Reach has both low and high tides. A braided river has bars and a meandering system of smaller channels.

The braided North Reach, provided a sustainable economy for tens of thousands of years. When European settlers arrived, they sought to channelize the river; by eliminating many of the lakes and islands. The river was dredged and the dredge became the liquifiable soil we now find on the riverbanks. The banks were hardened and the once abundant salmon population shrunk to less than 1% of the juvenile salmon that existed in the braided river system.

Knowing the original shape of the North Reach, helps us to understand the challenges and potential of this part of the city.

Quick Lesson #5: Indigenous people of the North Reach and Peninsula

It has been a busy place that sustained life since time immemorial. There were numerous villages and summer homes. Many of Oregon’s tribes followed seasonal cycles of harvest and came to the lower Willamette River to trade, fish, gather plant foods, and see friends and relatives. Despite European disease, the Indian Removal Act and the Homestead Act, the tribes are thriving.

The best way to learn about each tribe is to go to their website or attend an event the tribe sponsors. David Lewis is an Indigenous historian who has written several books about the history of Indigenous people in the Willamette Valley. The Confluence Project is another good way to learn Indigenous history.

“Right to fish forever at all usual and customary places…” Treaties signed in 1855 with the Yakima, Umatilla, Nez Pierce and Warm Springs tribes require access to the river and that the river must support juvenile migratory fish. Many species of fish are threatened and endangered by actions taken in the North Reach, including the River Overlay Zones along the North Reach.

Every decision made in the North Reach and on the Peninsula, should include the critical question of how the city is honoring these treaties. “Treaties are the “supreme Law of the Land” under Article VI of the United States Constitution.

Quick Lesson #6: How did trappers change the North Reach watersheds ?

Before European based trappers made their way into the Willamette Valley, the rivers enjoyed an economically reciprocal relationship with the tribes. Seasonal rounds of hunting and gathering were complimented by trade and an understanding that caring for the river meant it would continue to care for all beings.

Trappers made their way into what is now Oregon, first on the coast to trap for sea otters and later inland, as international companies were created to trap beaver, river otter and mink. Millions of pelts were shipped to ports around the world in a frenzied desire for the furs. This began an economy of extraction. In an extraction economy as much as possible is taken to provide large profits to people who do not necessarily live in the place of extraction. There is little effort to sustain the commodity but rather to gather it as quickly as possible.

Because the beaver, otter and mink were integral to the ecological composition of the watershed, losing them meant that the landscape was changed and other species were put in danger. Today beaver can be found in the North Reach but mink and the river otter have not yet been able to establish themselves. It was not just the extensive trapping but the intolerance of their habitat by industrial lobbies that makes their return difficult, as they move on to other extractions.

Trapping in. the 1700-1800’s meant more than the loss of wildlife; trapping eventually brought missionaries and settlers. The Hudson Bay Company in Vancouver, led to the creation of settlement and a farming, livestock economy that further destroyed the native habitat. The river was seen as something to consume and alter to meet the needs of an extractive economy that saw this “new land” as a blank check free for the taking by those in power.

State land use laws, created decades later, attempted to integrate various land use needs with the intention that the guiding rules would work together in ways that the early trappers and their foreign companies could not imagine. An economy of inter-relationship.

Quick Lesson #7: North Reach watersheds and birds

Long before the city named a part of the North Reach an “industrial sanctuary” the lakes, streams and wetlands created a critical resting place for billions of birds in the Pacific Flyway. Migratory birds come from as far away as Patagonia, and move north to Alaska, many stopping at Smith and Bybee Lakes and Sauvie’s Island to rest.

We look up and see eagles and falcons, as they make their way from Forest Park to the river. Or maybe we take time from our busy lives, to watch the snow geese and sandhill cranes before they fly north. Perhaps we find ourselves holding our breath as the snow geese lift off the lakes and fly together at sunset. Perhaps in that moment we know the meaning of sanctuary in our city.

The Pacific Flyaway is one of four bird flyways in the United States; the Atlantic, Mississippi, Central and Pacific. Birds follow these “highways” as they breed and look for places to winter. The Pacific Flyway follows the Pacific Coast and goes inland to the Rocky Mountains. Migrating birds have long learned, through many generations, the routes to follow and the places to stop. Billions of birds follow these flyway routes and North Portland is critical to their successful migrations.

Resident ducks and geese supplied important food sources to Indigenous tribes and early settlers. Swan Island was named after the many swans found there. In the Lewis and Clark journals, they complained that the ducks and geese kept them up all night.

The North Reach, long before Portland built the industrial sanctuary, was and will be a bird sanctuary. In the past, lakes were filled and river banks were hardened. Pesticides caused near extinction to the eagles and falcons. The forever chemicals of the superfund made their way into the food chain. And yet the birds come and many stop and rest in the waterways of the North Reach.

Thousands of people before us fought for the lakes, for Forest Park, the slough and for Sauvie’s Island. We remember those who fought for the elimination of harmful chemicals in the food chain. The North Reach is not only a place of billions of birds flying overhead but a place of heroes who made sure there would be a place for the birds. We remember always, Bob Sallinger who climbed the St John’s Bridge to help save the peregrine falcon or Bob stopping mid-sentence to listen to a bird; to remind us to look up.

To learn more about the birds in the North Reach, explore The Bird Alliance, METRO, and Fish and Wildlife websites.

Quick Lesson #8: Forest Park and the CEI Hub

Driving down Highway 30, the Maple Trees of Forest Park glow golden in the afternoon sunlight; the creeks are beginning to sing with autumn’s first rain. The mushrooms appear, as gifts from moss covered fallen logs. Ancient trails lead us up into a world that wraps its arms around us with a peace we dared not believe was possible within a city.

On the river side of the highway, we squint into an imposing wall of steel and steam. A nine-mile stretch of aging oil tanks placed precariously on rivers edge. The forest and the CEI hub side by side. The hundreds of creeks driven underground through dark tunnels, slowly make their way to a river, long -polluted with industrial waste and declared a superfund site.

Highways and train tracks separate the river from the forest. They are no longer considered two parts of one watershed. The trees that once shaded pools of juvenile fish, are banned by city code. Though divided now, the Tualatin Mountains, Forest Park and the river are one ecological system. The Tualatin Mountains emerged though millions of years of seismic and volcanic activity, fault lines and shifting tectonic plates. The forest provided the Indigenous people with fiber, food and medicinal plants. Since time immemorial the forest and river were cared for through a sustainable economy.

Settlers logged the forest twice. Ancient douglas fir and cedar filled the river as the trees made their way to mills and foreign ports. The small river towns grew out of the forest economy of logging and mills. Small, wooden homes built on the edge of gullies and creeks and forested paths. Immigrants from around the world, grateful for work. Farms and small businesses intertwined.

In 1948, the city dedicated Forest Park which now includes 5,170 acres in the city. It is home to over 110 bird species, countless reptiles, amphibians and mammals. Each day, Portlanders and guests from around the world, wander the trails in awe of this remarkable urban park. As they make their way to their car, walk over the bridge or wait for a bus, they cannot help but notice the contrasting stand of large oil tanks only a short distance from the forest. Tanks teetering close to the rivers’ edge. Oil trucks and trains speed by. There are signs, warning of gas pipelines. The visitors wonder about the hub of tanks placed so close to the forest and river. What if there is an earthquake? A fire?

The maples glow in the cool autumn sunlight as the river fills again after a warm summer. Eagles call to one another as they return to their forested homes. The salmon return to their natal streams. The collective governments sigh and shrug their shoulders. A forest, a tank farm and a river side by side in Portland’s Northern Reach.

Quick Lesson #9: Clearing the land of trees, people, and their communities in the North Reach

We have spoken in this primer of the extraction of the animals, the plants, and the water of the Northern reaches of our city. But it is more; the industrialists who came here from Eastern cities looking for great wealth, needed to clear the land of the people. The cycles of human removal have taken many forms over the last two centuries; using laws and codes to support an extraction economy. An extraction economy that includes people and their communities.

Often, we are told that it is for their own good or for the greater good of our economy that the prosperity will trickle down. Perhaps not equally, but the overall benefit outweighs the concerns over extraction. This human extraction took hold with the introduction of disease that accompanied the trapping era. Diseases that indigenous populations had no immunity to, swept over the area.

Health and safety issues almost always work hand in hand with an extraction economy. Coal mines and factory smoke; malnutrition and child labor. In the North Reach, disease left the tribes weakened, but not destroyed. Those who remained were forced from the land and placed on reservations. Most of those in the North Reach were sent to the Grande Rhonde. Tribes, that had since time immemorial cared for the land and water, were forced onto reservations across Oregon. New settlers moved in.

The stolen land was given out through the 1850 Homestead Act. White men were given 350 acres and if they were married another 350. Single women, Indigenous, Chinese, Black, and Pacific Islanders were excluded from getting land in Oregon. In this way, white men were the first to make claims. Many of the early claims were not made by farmers, but investors who hoped to make a fortune in the west. Later, many immigrants made their way to Portland in covered wagons and worked to buy smaller plots of land from the first investors. Seeking safety from prejudice, they often sought refuge in the smaller villages of the North Reach, which was not yet a part of Portland.

These immigrant communities worked to set up small towns, dairies, orchards and cultural traditions. They fished in the river, hunted and worked in logging camps. They built schools and parks and churches. They worked in our factories and built ships but when the logging was no longer as profitable and the ships no longer needed building, the small towns were torn down, roads expanded and lakes filled.

Thousands of people in the North Reach villages were forced to leave due Japanese Internment in 1942, Vanport flooding in 1948, road construction, changes in zoningm and the quest for a fossil fuel storage economy. The people were removed, houses dynamited, and businesses closed. The cycle of removing people became a signature mark of North Portland culture. When industry wants your fish, your trees, your farm land, your homes and businesses, they will find a way. This is the story of many generations in North Portland, who despite this are resilient and loyal to this land between two rivers.

Quick Lesson #10: Dredging the Willamette River

The Lewis and Clark Expedition canoed past the mouth of the Willamette River not once but twice. The entrance was intertwined with small islands and sand bars. It was perfect for migrating fish, wapato, wintering ducks and many more gifts of the natural world. The river hadn’t needed a lot of remodeling, but when the industrialists arrived, they could quickly see that this winding, “swampy” river would never do. Those who stayed and did not head south to look for gold, were determined to rebuild the river as a deepwater seaport. They dreamed of being the greatest seaport on the west coast.

Never mind that it was over a 100 miles from the sea. Using political influence and dreams of great wealth, the river began to be dredged as early as 1865. The river was reported to be 12 feet deep; although there were those who told stories of walking across it. The goal was a deep sea channel from Portland to the ocean, with Portland serving as an inner harbor for wheat and timber.

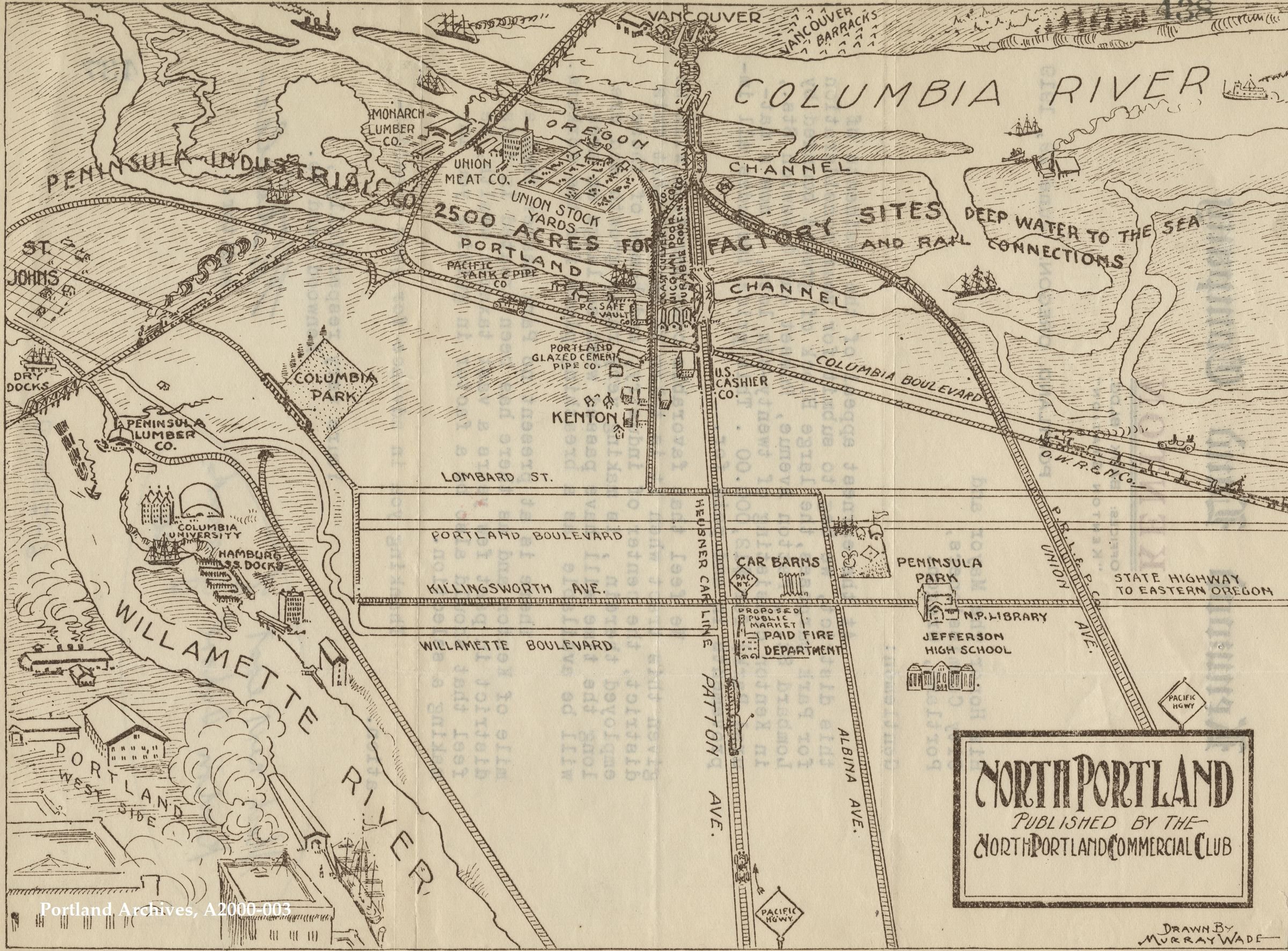

By 1871 the Army Corp of Engineers had arrived and dredged the river to 17 feet. In 1891, the Port of Portland was created to manage the ongoing need to dredge the river. Today the North Reach of the river is maintained with a 43 feet deep channel.

Where to put the dredge material and what could be placed on top of a piece of land created from the bottom of the river was not seemingly a problem. Dredge filled in the 250-acre Guilds Lake. Dredge lined the river banks and Swan Island was an island no more. The airport, Oaks Park, and much more were built on dredge from the river bottom.

At the time, this must have seemed perfect. Creating land for free from the bottom of the river! Decades later, we would face the consequences of unstable soil as well as what was placed on top of the soil. Industries were built on riverside dredge and their waste dumped into the river, leading to cancer risks, poisoned fish and a 1.5 billion dollar superfund cleanup. Still others thought it a good idea to put large oil tanks on the dredge which now leads to the probable need to move them off of the dredge which is predicted to fall back into the river when there is an earthquake. Flooding issues and endangered species protection are mostly left for another day.

Portland has long stopped logging Forest Park and most of the wheat is shipped from Ports on the Columbia. The famous Dredge Oregon sill sits in the harbor, ready to maintain the shipping channel and hardened banks. The once braided river is now a 43-foot channel. The dredging, the superfund clean-up, the possible CEI harm, the health and safety risks are, in part, financed by the tax payer. River overlay and set back codes assure that the river stay in its channel, held in place precariously by a hundred years of dredge material. Understanding the changes made to the river channel, helps us to understand the challenges facing the North Reach.

To learn more walk across the St Johns Bridge or look out from a bluff along the east side of the river. The blog post” How Deep is My River” is a great read. Old maps are fascinating. You can reach me at sarahsojourner@mac.com with comments, questions, and suggested topics.

Bonus Lesson: Northern Red-Legged Frogs

As the much loved frogs protestors spread across the country in a unified call for our democratic ideals, the real frogs of Portland, most notably the red-legged frogs, continue their cycles of migration from the forest to the river and back again as they search for wetlands and ponds necessary for laying their eggs.

Like their counterparts being endangered by ICE officials, they face the harm of crossing Highway 30 as they leave Forest Park and look toward the river. Trucks and cars speed by on a four lane highway. Oil trains pass by. Their hereditary path cut in two, but like our frogs at the ICE facility, they remain strong and resilient. They continue their journey not for themselves, but for future generations of frogs. And like our frog protesters, the frogs cause has been uplifted by volunteers who both advocate tor them and help bring them to safety, not unlike our frogs at the ICE Detention Center.

By Walter Siegmund (talk) - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=6691137

Quick Lesson #11: Juvenille Salmon

Protecting salmon in the State of Oregon means we have to be sure juvenile fish can make their way through the North Reach of the Willamette River. Juvenile salmon are about the size of your little finger. When they make this journey and our current policies don’t make it easy on them. They often arrive with spring flooding and may even be traveling backwards.

The juvenile salmon need a riparian habitat with cool water and trees for much needed rests and nourishment from macro-invertebrates. Instead, these juvenile salmon often face hard bare banks, decaying docks, and no sign of riparian cover. They can’t simply cross the river and find habitat on the other side. These little fish need it to be available on both sides of the river, consistently throughout the Portland Harbor.

To maintain our already low salmon population, we need their value to be included in planning documents with codes that support riparian habitat in Portland’s industrial areas. There is no evidence that vegetating our river banks will hurt the economy. Toyota’s car lots have a generous riparian habitat and are one of the busiest docks on the river.

Several species of salmon, as well as the green sturgeon and shellfish, are on the threatened and endangered species list for the Portland Harbor. It is estimated that our spring chinook salmon run is about 1% of what it was historically.

Our treaties with the tribes obligate us to protect the salmon and allow access for fishing. Every time a river decision is made we need to ask how it will support juvenile salmon and other endangered species. Tribal fish experts as well as Oregon’s Department of Fish and Wildlife can be consulted on these decisions. The River Overlay zones, the Tree Code, and the Economic Opportunity Analysis all need to be viewed through the lens of the salmon.

Both commercial and recreational fishing contribute billions of dollars to our economies as well as providing a valuable food source to families. Salmon can be seen as an indicator species. If the salmon thrive, then it is more likely that we are addressing climate change, assuring clean air, creating healthy rivers, and respecting our city’s cultural heritage.

Resources: Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission and US Fish and Wildlife Services

Photo courtesy of NOAA.

Quick Lesson #12: Contaminated Fish in the North Reach

Many industries along the Willamette River poured or leaked toxic chemicals into the river. The chemicals turned out to be “forever chemicals” that caused death and health problems for the people along the river who ate the fish.

The chemicals sunk deep into the sediment. When the macroinvertebrates ate the contaminated matter and then when the fish ate the insects, they became contaminated as well. When humans fished, as they always had, they risked exposure to many health problems. Pregnant mothers and young children are at the greatest risk. All in a place where people had fished since time immemorial. A place,where people depended on fishing to feed their families.

Most of the owners of the factories have moved on, leaving acres of brownfields and the Portland Harbor as one of the most contaminated superfunds in the country. The superfund plan requires dredging or capping the contaminated soil.

The resident fish and shellfish are the most at risk as the migrating salmon spend less time in the North Reach. Catfish, carp, bass, and clams are a particular risk.

Chemicals include PCBs, PAHs, DDT, dioxins, arsenic and pesticides. Multnomah County has taken the lead on educating the public about the harms of eating fish in the North Reach. A tax payer funded city grant also helps with this effort. According to federal law, the potentially responsible parties (PRPs) are responsible for the clean-up.

In the North Reach, the lines at the food banks grow. The access to fishing docks shrink and fewer salmon make their way to the sea. Many immigrant communities fish in the river and need help with translation and understanding the risk.

Multnomah County Health Department is the best place to get information about the fish advisory in the North Reach. Contact sarahsojourner@mac.com with comments. The entire series can be found on the Braided River Campaign website.

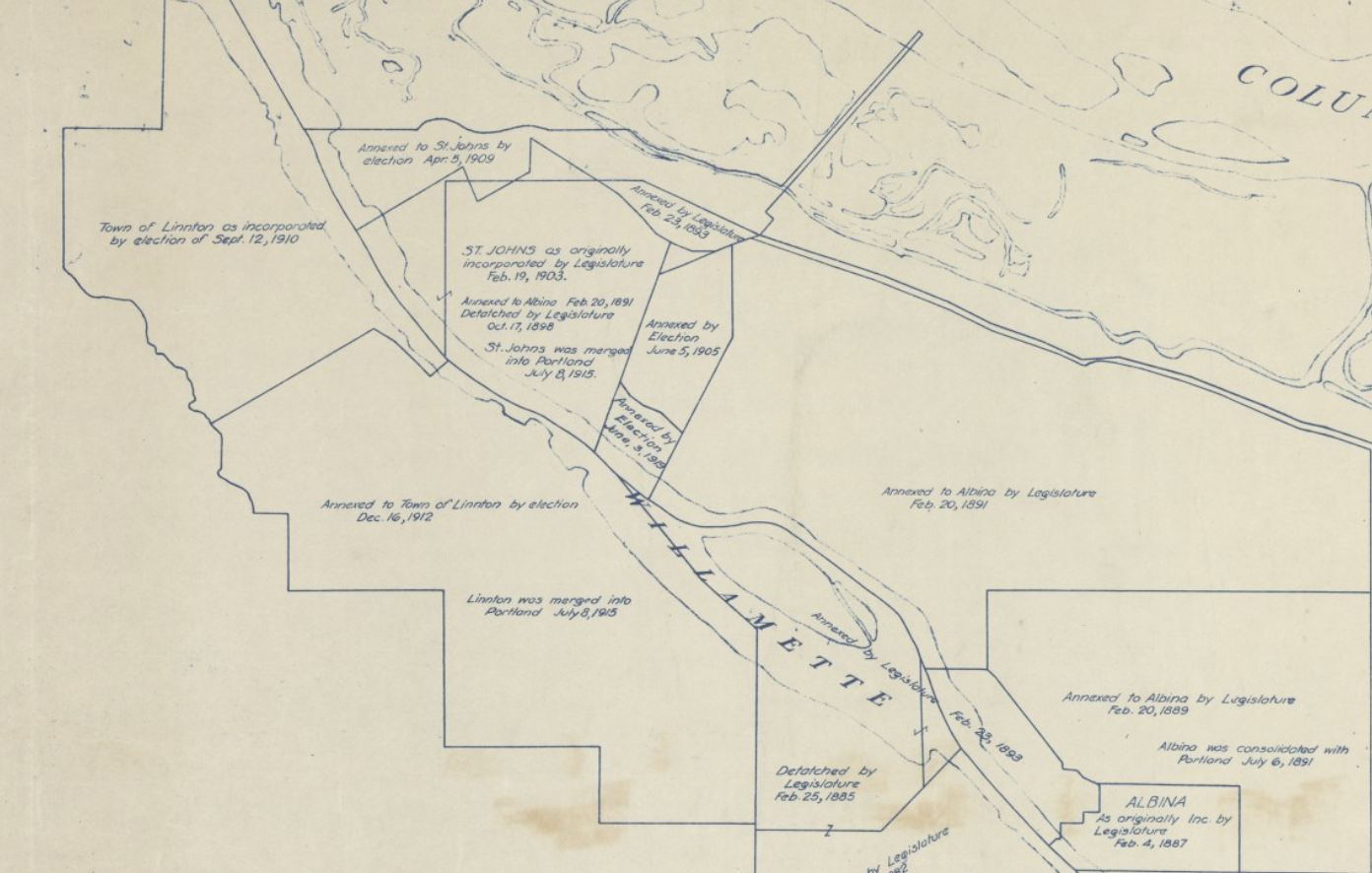

Quick Lesson #13: Annexing the North Reach

For most of Portland’s history, the wealthier central city annexed its primarily working, immigrant neighbors to increase their population, acreage, and control of the riverfront. The lands to the east were composed of small villages made up of farms, fishing docks and timber operations. Many of our current neighborhood associations reflect the names and locations of earlier towns and hamlets.

Albina was a large city; far larger than Portland and extended all the way to the Columbia River. St. Johns was annexed by City of Albina in February 1891. Albina, along with East Portland was annexed in July 1891. St. Johns seceded from Portland in 1903. Linnton and St John’s were annexed by Portland in 1915. I have heard historians debate the legality of these annexations which were supported by those with the potential to gain the most. It is doubtful that residents understood that they were voting away their ability to fish.

In all these communities, large highways divided their towns as core services and cultural identity were laid to ruin. Promises were made and promises were broken. The Railroad Cut divided St Johns in two and Linnton watched half its town be dynamited and never replaced by the river, as once agreed on.

It is unlikely that they understood that flammable oil tanks would replace lakes and that creeks would be driven underground. Through a process of annexation, industrial zoning and the power of eminent domain, these annexed neighbors became the bank account for some of our wealthiest citizens. With few environmental regulations and deep ties to city council, the shores of the North Reach Watersheds were fair game as those who lived there tried to hang on. It was accepted then and now that these annexed siblings would provide, not only their land and waterfront but the labor. They were expected to be grateful in a system of trickle -down economics.

For almost all of Portland’s history the city council was represented by those who lived on the inner westside. It is only now with a new form of a representative city council, that the annexed communities are beginning to have a voice. The ecological, cultural and social damage to the North Reach will take decades to repair.

Information is hard to find but try the Braided River Gallery window display at Lloyd Center or the article Bleeding Albina and occasional tours. Neighborhood websites. You can reach me at sarahsojourner@mac.com. These posts can be found on the Braided River Campaign website.

Quick Lesson #14: North Reach and the Military

From the time European Settlers landed in the area, it was a military operation. There was the Corps of Discovery with Lewis and Clark from 1804 to 1806 which was a military operation that camped along the Willamette and Columbia Rivers. Russia, Britain, and the United States were competing for the Pacific Northwest until the Russo-American Treaty of 1824.

The United States military followed, setting up forts to assure the domination of the land over the tribes. This was often done by force and instigation by the troops. Fort Vancouver, established in 1825, was a military fort even as it was a trapping operation. The Oregon Trails of Tears in 1856 were supervised by the military. The Army Corps of Engineers pulled in to dredge the river in 1866; in part for military purposes.

Jump to World War II when the Willamette River was used to build ships for the war. The military-industrial complex dug in, changing the river, the river banks, and the population. Thousands came from across the country to participate in the Kaiser war time industry. When central downtown Portland did not want the ship builders living near them, housing was built throughout the North Reach. Books have been written about the post-war life of the housing and the people. Red lining, floods, tear downs, and urban renewal swept over the once busy shipyards. Old ships were taken apart and dumped in the river. Jump to Vietnam, where Agent Orange was manufactured in Portland on a now highly polluted brownfield.

Today the North Reach is home to the Coast Guard and numerous training and National Guard units. In the last few years, military troops have been in Portland over on-going struggles over the Bill of Rights. Military ships are a key part of the annual Rose Parade. ROTC is part of many schools. Veterans continue to struggle and face long term health problems in the Portland area. The Veterans Hospital is part of the OHSU campus.

The military, in many forms, made an imprint on the North Reach.

Photo by Petty Officer 1st Class Levi Read

Quick Lesson #15: 8,605 acres in Portland are contaminated with brownfield constraints

The first time I looked out at the North Reach, from high up on Saltzman Road, I was in awe. Acres of fields beside the Willamette River with snow covered mountains in the distance. A beautiful pastoral view in the middle of the industrial area. Only, as someone pointed out to me, these fields are brown and barren and unlikely to grow even a blackberry bush. They are brownfields. Places where past industrialists deposited contaminated materials and then, when faced with the cleanup, often walked away. Sometimes the owners can be found and sometimes they have left town and the sites are designated as “orphan sites.”

The brownfields of the North Reach sit and wait for someone to take a chance on them. Or the city waits for the taxpayers to pay for the necessary cleanup so they can redevelop them as more industrial sites. Old cars, Agent Orange, DDT, creosote, PCB drenched electrical parts, barrels of bright green chemicals. Filled lakes and creeks oozing with things that in days past killed all the frogs and left scores of beavers dead on the shores.

I’ve met elders who once fished at Doane Lake and remember the dumping of chemicals. I’ve sat with a woman who camped there with her family during the depression in a Hooverville site. This land has stories too.

The question has come up many times regarding who “owns” a Brownfield, if tax payers directly or indirectly pay for the monitoring and cleanup. Should it be ”given” to out-of0state corporations or let to go wild? Does the community who bore the risk of the contamination have a say in the redevelopment? What role should the tribes have in the decisions?

Standing by the railroad bridge next to Siltronics in NW Portland, we look across at three Brownfields in the journey of repair and restorationL the River Campus at the University of Portland, the potential Botanical Gardens, and the METRO-sponsored Willamette Cove Nature Park. All will be connected with the North Portland Greenway Trail. It is not easy. The contaminated soil often has to be removed and replaced with new soil and plants. “Hot spots” have to be capped and monitored by Oregon’s Department of Environmental Quality forever.

This, too, is the North Reach. Acres of empty, contaminated fields. When a person leaves their garbage on the street, the public is outraged. When corporations left their garbage, rotting docks. and acres of cement structures, it took decades of lawyers and agencies to even try to hold them accountable. The Brownfields of North Portland are mostly out of site; down rivers with no access and along deadend roads and railroad tracks. Community members who advocate for the cleanup of North Portland’s land and water are often met with hostility. Advocating for prevention may be seen as anti- business, even as the contaminations cost is in the billions of dollars.

Learning more: The City of Portland and State of Oregon have webpages devoted to Brownfields. Or stop and look out from Saltzman Road or along Willamette Blvd. Explore the web pages of the Portland Botanical Garden or the Willamette Cove Nature Park for some positive movement to repair our city’s Brownfields. Read “Council Watch – Banking on Brownfields” for a look at how taxpayers could indirectly pay.

Quick Lesson #16: Oil trains in the North Reach

When Darcelle XV was a little boy growing up along the shores of the North Reach, a passenger train from Portland to Linnton passed by his house. Born Walter Cole in 1930’s Linnton, his father worked in a lumber mill and he ran, as the North Reach kids did, from forest to river in a mosaic of endless adventures. In his biography, he recalls taking the train to Portland with his mother to watch a movie. When his mother lay dying, young Walter raced across the train tracks to get his father at the mill.

A passenger train to Portland has long since been replaced by an endless stream of black, oil trains. The road he easily crossed is now a four-lane highway, filled daily with a parade of tanker trucks. Most of the crosswalks and traffic lights have been removed and no child dares to cross the road. The river and the forest are separated by one more threat to their very existence. People taking TriMet cling to the side of the highway as the industrial privileged speed by. Their speed a priority over safety.

The black, oil trains line the small town, parking by the community center. Separating the community from the river. Although one can read the placard to discover the contents, there are too many and even knowing the contents doesn’t seem to change policy. For a time, after an oil train exploded in Mosier, people rallied against their presence in urban neighborhoods and yet today, there are more than ever.

Portland City Council passed a resolution in 2015 opposing oil-by-rail, but we have only seen an increase. According to DEQ, 380 million gallons of oil come into Oregon by rail each year. Rules were made to only allow 30 cars at a time, but not a limit on how many trains. Experts say the Blast Zone is one mile in any direction. The trains, running along the river, would most surely spill into the river and destroy life as we know it on the North Reach.

As industry tries to sell us more biofuels, the trains will carry the still flammable fluid into the North Reach to be unloaded into tanks and then into oil trucks to be distributed. All within footsteps of Forest Park, the river, and neighborhoods. The city government shrugs, claiming to be powerless against Interstate commerce. They take their chances there will not be an accident or an earthquake. There are fires; sparks from trains, a turned over truck, a tossed cigarette, a brush fire.

Although the CEI HUB tanks have drawn much deserved attention, the movable tanks, the tanks on wheels that speed by with little regulation, are part of the North Reach annexed landscape. But the city made the North Reach an “Industrial Sanctuary” and that gave rise to a city that hosts oil tanks on wheels to feed the great tanks that are the signature landmark as you enter our city’s harbor. As long as the tanks exist, the trains and trucks will support them.

The little boy, known in Linnton, as Walter Cole remained a faithful supporter of his childhood home. I saw him there when the community tried to implement a neighborhood river plan. We traipsed through the growth to the river and dreamed. I think of that little boy riding the train to the movies in Portland ; his mother who would die too young and the oil trains that would displace the passenger service. In the Oregon Encyclopedia Page written about him, they say he grew up in “scrappy Linnton.” When you label a neighborhood scrappy, how easy is it to park explosive oil trains in a place time forgot.

It is painfully difficult to find accurate data about all liquid fuel on trains and trucks, including how much is exported, But if you drive Highway 30, they are everywhere.

Photo by Mike Krzeszak.

Quick Lesson #17: The Railroad Cut – A scar in the heart of North Portland

Remember playing Monopoly and everyone wanted to get all the railroads? That’s what was happening on the North Portland Peninsula after Oregon became a state in 1859 and the Homestead Act of 1862.

Businessmen from around the country headed west trying to establish railroads because railroads meant power and wealth. The US and Oregon governments were granting railroad easements and 20 miles of land in either direction. What they couldn’t get for free from Indigenous land, they got through public domain laws.

If you look at a map of the peninsula, you’ll see it’s surrounded by railroads on all sides, down the middle and over into Guild’s Lake and Linnton. Early on, there was a need for passenger train service, but the goal was to ship wheat and timber and later to include oil-by-rail which eventually outweighed much of the local passenger trains.

With power and wealth driving urban planning, St Johns was cut in half with a railroad shortcut that connected the Columbia and Willamette Rivers and included the railroad bridge.

Owned by BNSF Railway and dug in 1907, it was designed by James Hill also known as “The Empire Builder,” despite the objections of the neighborhood. Chinese laborers were brought in and the story goes that if they died digging the 80-foot gully and tunnels, they buried them there in the “Cut”. The Cut is composed of an underground tunnel off of Columbia Blvd that connects to the deep railroad-filled gully. Both destroyed homes, farms, and businesses so that the trains could go faster and save time.

After coal trains passed through, in the depression, children climbed down the steep banks to collect coal that might have fallen to heat their homes. Eventually the land beside the Cut became the Cross-Peninsula Bike and Walking Trail, but the city has has its eye on taking this too. The trail became a large tent community during the pandemic and now houses a Safe Village. For a time it was home to the Belmont Goats.

The Cut is a place of legends and open wounds to the land and people of the North Reach. The aging bridges over the Cut are the only way of leaving St Johns, leaving the community without an escape plan in the event of an earthquake. It is a major route for oil-by-rail, despite being in the Blast Zone of many homes, schools, and businesses.

Walking along the Cut, there are some beautiful old trees. I think about the person who planted them. I think about the workers buried in the deep artificial gully and who this benefited. In the city’s theory of trickle-down economics, the price these people paid was worth the benefit, but I wonder if they were ever asked.

For great information, go to Slabtown Tours web page and read the article Tonya March wrote about the “Cut”. If you park at St Johns Fred Meyer, you can walk a block to the east and gaze down at the tracks, then walk the Peninsula Trail to Willamette Blvd where you can look down at the Railroad Bridge, and the acres of Brownfields created by the city’s past economic policies. A lot has been written about it, if you poke around.

Quick Lesson #18: The Haunted Docks of the North Reach

Before docks, there were clearings with low lying branches or a fallen tree to grab on to. There were warm, sandy beaches and a place to pull up a boat and make a small fire. Places of trade and local commerce. Places, since time immemorial, where Indigenous people lived within a river economy of reciprocity.

Today, the North Reach is a graveyard of these places and the people who once pulled their boats ashore and found comfort in the ripple of water. A wooden grave yard of lost community docks where local farmers and craftsmen could bring their products and unload merchandise. Docks accompanied by stores and saloons and barber shops. Places of community and small business.

Now, the North Reach of the Willamette River has two public docks at Cathedral Park. The other dock at Swan Island has been closed, though it served the inner Northeast neighborhoods for decades. A great place for sturgeon and swimming. A place you could ride your bike to and swim in the summer. Polluted but still water and dock, there is a for sale sign next to it.

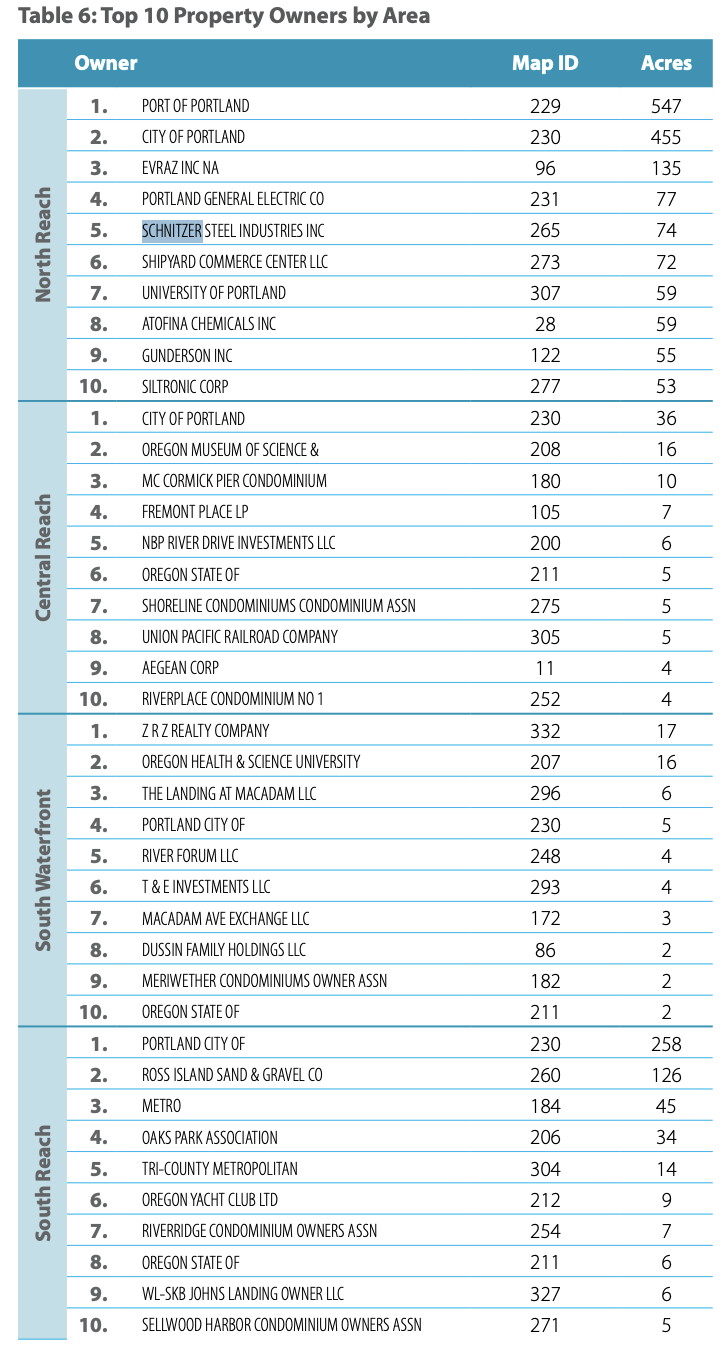

Despite the state’s land use laws that declared all beaches public and required the cities to carve out a Greenway along the river, the industrialists found a way around it. You can use the beach but you have no way to get there. Joke’s on you. Despite the fact that the majority of the North Reach is owned by the city and the Port of Portland, the docks and “public beaches” are reserved for deserted docks and empty pilings. Saved for the romanticized past when influential families made their fortunes on the back of the North Reach communities.

The current North Reach waterfront was created by two critical legislative actions. In 1892, the state created the Port of Portland. Just thirty years after the Homestead Act of 1862, the industrialists knew they had to do more than get free land. They had to control the river.

The Port of Portland was given the power of eminent domain and could force the sale of any riverside land they felt they needed for their purposes. Small docks and a market economy gave way to larger and larger industries along the river. The farmer, who had a wood lot and brought a few trees to the mill, was displaced by large forest exporters. The city created the Commission of Public Docks in 1910, which later merged with the Port of Portland in 1970. Docks became terminals with large cranes and fences. When industries closed, they left the docks and pilings to rot and age over the years. At low tide, we see a vast landscape of old deserted docks; the owners having walked away decades ago. Community members did fight for access to docks and to union jobs, but the depression and World Wars left the area powerless against the impact of the military-industrial complex.

Docks are overseen by the Oregon Department of State Lands and as long as an owner pays a fee, the unused docks and terminals can stay forever unused and out of the reach of the public. I once took a group of students by these docks who, with shock, remarked that they looked haunted and scary. Miles of unused, decaying docks, which lie in perpetual disuse as part of our “working waterfront.” They are kept out of public use in case some industrial giant should one day want them.

It is easy to see how, when fortunes were no longer being made on timber and wheat, oil companies were give so much of our riverfront. Through public domain laws, the Port of Portland and the city can force the sale of land, upzone it, and sell it. Decade after decade, the city’s Comprehensive Plan, the Economic Opportunity Analysis and purposefully “agnostic” heavy industrial codes leave the North Reach a place of deserted, haunted, decaying docks. The rallying cry of industrialists is not one inch for trees, fish, trails or community.

Is there room in the North Reach for a lazy, summer day in a canoe or for a child to learn to fish from a dock? On a hot summer day, will the river welcome those wanting to swim and will tress protect the juvenile salmon? Can jobs and public docks once again co-exist within the river as the haunted docks of the North Reach make peace with their past and welcome a new vision?

Gratitude to the Human Access Project and SOLV for tirelessly cleaning up the decaying docks and advocating for new public docks. hanks to The Mosquito Fleet for creating a model of free public access to kayaks at Green Anchors. And to all those in all levels of government who work to heal the harm and inequities of the North Reach. To METRO for the Willamette Cove Nature Park, a pearl of hope.

Heading out? Go to the Dockside Tavern, on Front Avenue for a look at the former dock culture. This local bar and eatery survived the construction all around it. If you cross the street, you can walk out on the path created for the upzoned condos. From there you can see some evidence of the old docks. Head to Cathedral Park at low tide or try to find the old docks at Swan Island.

Quick Lesson # 19: World War II Shipbuilding and Deconstruction

Few things altered the North Reach as much as the construction of Liberty Ships during World War II. The government ordered one ship to be built and launched every day! Over 600 ships were built on Swan Island, St Johns, and Vancouver with many other smaller factories providing support roles. Highly dangerous materials were used in the construction and deconstruction of these ships. Thousands of people would die over the subsequent decades, mostly from asbestos. The thousands of people who came to work in the shipyards and decided to stay, faced discrimination.

Many of Portland’s wealthiest patrons and families made their fortunes on the back of these workers who, after the wars, were marginalized through red lining, discriminatory zoning, and urban renewal projects.

There is little to remind us of this piece of history, no parks or memorials to those who died building and taking apart ships. At Kaiser on Interstate, there is a small sculpture in the courtyard in recognition of Henry Kaiser’s role in the shipbuilding operation. In Richmond, California a historical park was dedicated to the women who worked in the shipyards, The Rosie the Riveter/World War II Home Front National Park.

A distinguishing characteristic of Portland’s North Reach is lack of public parks and monuments telling the stories of people who lived there. And so the Portland Harbor Superfund serves as a monument with the former shipbuilder giants fighting to stop the clean-up of the contamination. The monument becomes the poisoned fish and the refusal of industrialists to plant trees.

We remember the labor and lives of those who worked in the North Reach Shipyards as the City seems determined to further marginalize the area by protecting Guild’s Lake Industrial Sanctuary, flammable CEI Hub tanks, and ignoring high asthma rates.

Determined to continue the path to ever increasing wealth, the former ship building giants and their allies become an informal collation to keep the workers and their children employed in their factories and warehouses. They are told these are good jobs. That the City and even the state and the region are dependent on the people of the North Reach knowing their place in the greater economic plan.

The contamination is particularly harmful to women and young children. It is multi-generational and causes learning disabilities and childbirth complications. The state and city knew about this decades ago. The EPA declared the Portland Harbor Superfund in 2000.

Learning more: Read /Listen to OPB’s “Portland’s Toxic Graveyard for World War II Ships.”

Oregon Shipyards Co. in St. Johns

Quick Lesson #20: The Legacy of the North Reach Ship Building Industry and today’s Economic Opportunity Analysis

Over 160,000 people moved to the North Reach Watershed between 1941 and 1945. They did not move to Portland proper, but to the recently annexed communities of St Johns, Linnton, and the Columbia River. They came from all over the country; people who wanted to support the war effort and find opportunity. Women made up 30% of the workforce. The Black population, in Portland, went from 2,000 to 22,000. An estimated 40,000 Indigenous people from all over the country left reservations and to work. They worked around the clock to build Liberty ships in record time. Henry Kasier supplied housing, daycare, food and healthcare so that they could all keep working and work hard they did.

And then World War II was over and the Portland “proper” did not want the ship builders to stay. It is not the ship building that determined the North Reach’s current situation, but rather what came after. It was the policies built around this population. What they did with the ships, but even more importantly what they did with the people and how the city government strove to keep the wartime wealth a forever benefit of the few.

On Monday November 10th, the comment period ends for the Economic Opportunity Analysis (EOA), a state required process of the Comprehensive Plan. Much of it focuses on the North Reach watersheds and how to protect industrial lands; to protect the wealth inherited during the war industry. Most people in the city know little of this process or the deadline to comment. Little do they know that clean air and tribal rights and good jobs are on the line.

The “gate keepers” of the World War II Industrial boom traditionally are key authors of this analysis. The formula that made their grandparents rich has to be maintained with free or inexpensive land, a disregard for the environment, and cheap labor. If anyone should suggest that perhaps this is not good for the grandchildren of the ship building industrial boom, they get out tired statistics that claim the working poor need whatever the newest version of shipbuilding is for the wealthy.

I understand how Portland families got into their businesses taking apart ships and throwing parts in the river, but how did we get from wartime housing to not a few oil tanks, but 650? How is it that we can take apart hundreds of large ships but can’t imagine how they could ever take apart empty oil tanks? How does a city that made a ship in a day lack the imagination to create an energy plan that does not put the river and the people of North Portland at risk? Henry Kaiser did not shrug when asked to build ships, but our city shrugs when asked about the oil tanks. We can’t even begin to imagine how we might create a safe energy plan. We can’t begin to build safety into our economic opportunity.

I have come to see the EOA as a modern-day land grab. Maps are drawn, highways planned, and zoning codes stamped onto the resting places of juvenile salmon, on people’s houses, and farm lands. It was not the ship building industry that wounded the North Reach, but what came after, what is still happening today. It is the city’s long history of classism that placed workers’ homes on wetlands and riverbanks in North Portland and red-lined neighborhoods for decades later. That “grey-lined” North Portland as an inevitable place for the CEI Hub and the newest warehouse industry. The legacy of post-World War II industry lives on in the North Reach and in an EOA that refuses to acknowledge its past. It is true that many good jobs came out of the war industry as they moved onto new peacetime products and services. This can be appreciated while acknowledging the harm and the future risks of other dominating industrial pursuits.

Goal One of the Comprehensive Plan calls for community involvement. The City of Portland annexed the North Reach and never stopped making good on its conquest and its right to these lands and water. What the North Reach has always been denied is true agency to create safe, healthy places to live and raise a family. After the wars, it became a sacrifice zone for the rest of the city. Instead of living between two rivers, being a blessing, it became a constant threat.

It was not the ship building jobs in the North Reach. It was what came after. It’s what’s happening today. It’s deciding what is good for the workforce of 2045 without asking anyone who is going to inherit it. It’s the legacy of entitlement and paternalism, not any one business mbut the underlying assumptions of a trickle down, extractive economy that has come close to sucking the life blood out of the North Reach.

To comment on the EOA, you have to go to the city’s Map App for the EOA. You can find many articles and resources on the shipbuilding workforce on line, if you want to dig in.

Quick Lesson #21: The North Reach is a food desert.

A cold, rainy November morning and the lines for the St Johns Food Bank stretch around the block. The Oregon Food Bank reports that that there were 2.5 million visits to Oregon Food Bank pantry’s last year. 110 million pounds of food were distributed. 1 in 6 people in Oregon receive SNAP benefits which is often complimented with visits to a food pantry. Almost every school in the North Reach communities is a Title I School, which means the children there experience a high level of poverty and instability.

How did we get here? How in North Portland did a fertile crescent of two rivers become a people and place dependent on food banks and federal funds for their food? How did the annual harvest of Camas and Wapato and an abundant harvest of fish and wildlife disappear in just 200 years? Why did the Market Gardens and Orchards tended by the Japanese farmers along Columbia Blvd disappear? Where are the farms of Skyline Blvd and the Chinese farms that lined Guild’s Lake? When did growing, gathering, and producing food in the North Reach stop being a core component of the economy? Agriculture is a category worth tracking in Portland’s economic reports instead of the quantity “shovel-ready land” available to be paved and made barren.

The Food Justice Movement works to ensure universal access to healthy, affordable, and culturally appropriate food for all and advocating for the the well-being and safety of those involved in the production process.

The elders of our community tell of great farms along Marine Drive and Columbia Blvd cared for by Japanese farmers before the internment of over 3,600 Japanese neighbors in Portland during World War II. People tell of all the beautiful farms and the orchards in the Columbia Gorge. The bounty of their work which they lovingly brought to market. When the War was over and they could go home, most of the farms were sold or stolen. Remember that the path to quick wealth is to seize opportunities to get land on the cheap. Some farms were saved by neighbors, but mostly the once fertile land was claimed by a post-war industrial society, systemic prejudices, zoning changes, highways, and freeways.

Once too, the lakes of the North Reach, along with the rivers, flooded and deposited rich soil for farming. Early settlers depended on farming. The Chinese had farms along Guild’s Lake, but their farms were burnt and the farmers chased out by the Ku Klux Klan in 1883. The hills above Linnton had dairy farms, orchards and backyard gardens. Only Sauvie Island survived the campaign against farm land, hunting, and fishing.

Although food security is the heart of a sound economy, Portland’s draft Economic Opportunities Analysis does not mention land set aside for agriculture. The assumption is that food will be delivered on trucks and trains to North Portland warehouses and distributed to ever diminishing, ever more expensive grocery stores. That the people will be given SNAP cards to buy the food. That the best jobs, are not those of farmer or fisherperson, but of a person who stocks warehouse shelves.

To grow food, we need pollinators. We need trees and flowers and bees and yet the opposition to the tree code, does not mention how the industrial lobbyists plan on feeding people; on growing and producing food.

The North Reach is a food desert. In an urban area, this is defined as an area more than a mile from a grocery store. Although there are a small cluster of food stores in St Johns, west of The Cut, there are none on the other side of Lombard all the way to the Columbia. All the way along Highway 30 to Scappoose.

City leaders fret over the lagging economy, but even if more people moved here, even if they can build thousands of subsidized housing units, what is the plan to feed them? The land most suitable for small scale farms, pollinators, and carbon offseta, is scheduled for shovel-ready development. Does an Economic Opportunity Analysis include an analysis of food production? No. Are agricultural lands and local food production, a part of a healthy economy? Yes.

Will we create an economic opportunity plan that supports the dignity of local farmers and abundant, safe fishing or will the North Reach teach its children that most food comes from large warehouses with food grown far from their neighborhood? Is agriculture part of our planned economic landscape? Part of a healthy community and education?

When you think of the North Reach, I hope you will try to picture the vast farmlands, gardens, dairies and fishing locations? Before the Critical Energy Hub, it was a Critical Food Hub.

Want to know more? Multnomah County created a Food Action Plan in 2015. The goal was “to create a sustainable food system that is affordable and healthy, based off a strategy of collaborative action and community participation.” Goal Three of State Land Use Planning calls for preserving agricultural land. Explore the many resources dedicated to the experiences of Japanese-Americans in World War II, including the history created by the Japanese Garden.

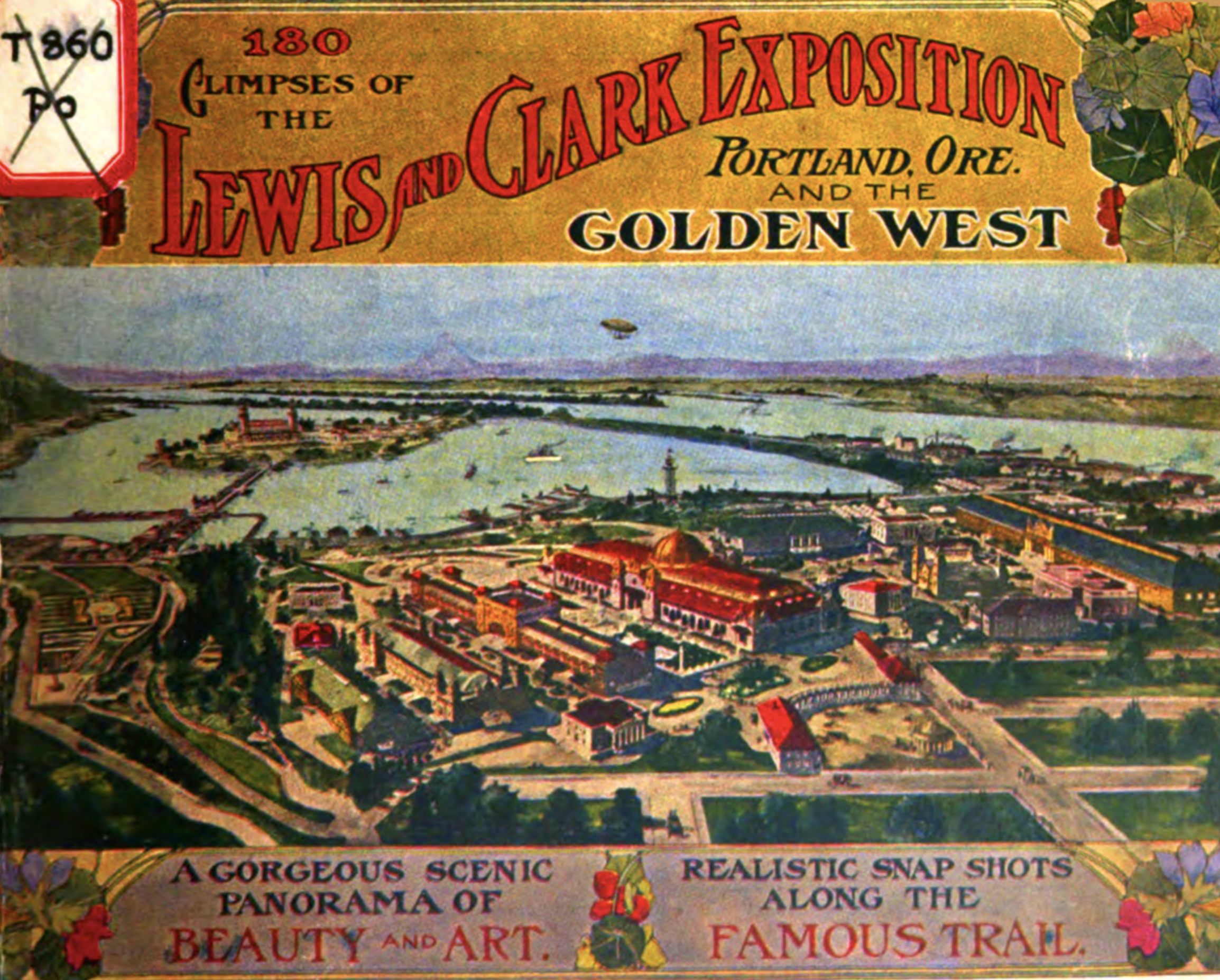

Quick Lesson #22: The Epic Battle Against Guild’s Lake

Guild’s Lake was located where the Guild’s Lake Industrial Sanctuary is located in NW Portland. Before there was an “industrial sanctuary,” there was the Guilds Lake Housing Community and before that the site of Portland’s World Fair. Well before that Peter Guilds’ homestead was located there and numerous small farms, including a Chinese farming village. And before that it was a place where Balch Creek made its way through forested canyons and tumbled into Guild’s Lake that was connected to the tidal, seasonal cycles of the Willamette River.

When the Guild’s Lake Industrial Sanctuary District was created in 2001, the historical perspective was that the Indigenous people had no use for the lake and besides 90% of the tribes had died. That is the city’s printed Indigenous history of the area. Most assuredly, the lake was an important source of plants, fish and other wildlife. That it was well appreciated, that wetlands were important to juvenile fish and all manner of life. Then and now we don’t always need to live in a place or alter it to place value on it. Guild’s Lake and the close by, Doane and Kitteridge Lakes, were valuable as they were. In economic value language, they were a powerhouse.

In the decades after Peter Guild first “claimed the area” in 1847, Guild’s Lake was dredged, filled with garbage, and filled with river bottom. Briefly it was revived to be the lake of the Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition in 1905, but no sooner did the fair end, then they returned to the battle against water.

To the industrialists dismay, the ship workers in World War II needed a place to live and given that they were not wanted in the City proper, they housed them on and next to what was left of Guild’s Lake. Up to 10,000 men, women and children lived in the area all the way across what is now Kittridge Bridge to the Willamette River. There was a school, daycare centers, and community centers. All torn down or moved as the battle against the lake picked up speed. The last building is the firehouse on the corner of Old St Helens Road and Highway 30. There is a new Forest Park trail across the way. I asked the Parks Bureau if they might consider naming the trail in memory of the lake. I was told by one park ranger that new people coming to Portland do not care about history or the old underground lake. Sigh.

The lakes and creeks never went away despite the effort of those who try to defeat them. It is difficult to win against a 250 acre lake and the surrounding water table. A man who works in the area tells us that sometimes he can feel the water underneath them. The pavement moves and the area floods. The creeks driven into culverts escape and cause problems. The contamination in the accompanying brownfields around Doane Lake have to be cleaned up. The stories of the people killed to make Guild’s Lake an eventual industrial sanctuary come to the surface sometimes. They too refusing to be forgotten.

Drive down Old St Helens Highway, follow the curve in the road. That is the edge of the lake. Notice the firehouse and then drive over Kittridge Bridge to where a large, Black community lived. Read the story in Street Roots, “Trauma’s Long Reach: The Homicide of Ervin Jones.” Remember one way to get inexpensive or free land is to scare people into leaving. Shooting a man through his window while he’s sleeping with his kids ought to do it. The policeman who shot him went on to be police chief. There was no justice. It’s close to where they built Zenith.

These are the lakes, creeks, wetlands, and lives that the CEI Hub tanks and Guild’s Lake Industrial Sanctuary were built upon. We are told the end justified the means, but perhaps the story is not over as the water lives on, waiting for the day it will once again see the sunlight. erhaps.

Visit the window display at the Braided River Gallery at Lloyd Center and read Tonya March’s paper on Guilds’ Lake for more information.

Quick Lesson #23: The Columbia River Lowlands – Floods, Levees and Earthen Berms

The North Reach of the Willamette River makes it way to meet the Columbia River with little public recognition or awareness. After traveling 187 miles through Oregon; gathering water from creeks and rivers, it provides the Columbia River with approximately 15% of its flow. The Columbia River’s last miles wind through a vast industrial complex. The final reunion is a whisper in our urban landscape.

The Columbia Lowlands were an ancient place of vast lakes and wetlands before European settlers arrived. Like the lakes along the Willamette River, the Port of Portland and industrialists sought to tame the area and bring it under their control. Of the three main lakes, Smith and Bybee exist. The largest, Ramsey Lake, was filled and now is the Rivergate Industrial District in North Portland at the confluence of the Willamette and Columbia Rivers.

In addition to the lakes and wetlands, the area has the 18-mile Columbia Slough that connects the Blue Lake region with the Willamette River. This system of lakes and wetlands continues on the Washington side of the river with Vancouver Lake and the Ridgefield Wildlife Sanctuary. Early developers sought to bring railroads to the area, creating berms and dikes and earthen walls to keep the water out when infill wasn’t enough to produce the desired land. The Cut makes it way through here, off of Columbia Blvd.

The result of these schemes was The Vanport Flood on May 30, 1948. Henry Kaiser, looking to build more housing for people working in the shipyards, chose the Columbia River Lowlands. At the time, it was not in the City of Portland. The federal government required wartime housing to be integrated and Portland would not allow it. (Remember the exclusion laws and red lining.) Vanport became home to some 40,000 people. At the time of the flood, there were about 18,500 people, including many returning veterans. The lowest point of Vanport City was about fifteen feet below the water level in the river. 15,000 people were instantly without a home as the river poured into the basin and former wetlands. he legacy of death, discrimination, and displacement in an area never suited for a city, lives forever in Portland’s history.

The federal government required that the land that was Vanport be set aside for outdoor recreation and wildlife. Delta Park, the Portland International Raceway, and the Blue Heron Golf Course stand where Vanport was built. The Columbia Slough winds through the area. The land once owned by Port of Portland became Kelly Point Park in 1984. Smith and Bybee Wetlands Natural Area, the nation’s largest urban wetland, was created in 1990. It was expanded to include the land where contaminated St John’s Dump was located. The flood and the closing of the dump in 1991 altered the area, even as industry pushed the boundaries and moved eastward along the river. Pushed as far to the edge of the parks and wildlife areas as zoning allows.

The Columbia River neighborhoods were slowly annexed for industrial development. The South Shore Annexation took place in 1983 and the East Columbia Annexations began as early as 1977. The Columbia-Lombard Corridor Mobility Plan pours large trucks through St Johns and other neighborhoods. The annexed Parkrose neighborhood faces increasing development of warehouses. Remember annexation, with incentives, tax breaks, and zoning changes creates industrial land with a probable tear down of traditional neighborhood sources of housing, food and local businesses.

Currently the City of Portland is considering environmental zones in the Columbia River Basin. How much of the slough, the lakes, and the annexed neighborhoods should be protected from industry? In a backdrop of the Vanport floods, industrial lobbyists suggest that the jobs in the Columbia Lowlands are optimal for Portland’s undereducated people. A familiar song for Portland’s North Reach neighborhoods.

The Columbia Lowlands will be impacted by climate change as the sea levels rise. The fragile relationship the city has forged with this area, is not so different than Vanport. The Army Corp of Engineers designs and builds a vast earthen levee system to keep the Columbia River out of the historic lowlands. This is the basic system that flooded Vanport and New Orleans faced; the most vulnerable living there beneath the wall of water.

As the late, great Bob Sallinger said, “They just want to build larger, taller walls without regard to the health of the environment.” And one might add the well-being of the communities in the Columbia River lowland basin. Remember the flood plains are also supposed to restore endangered species; to create places water can flood- not just walls.

This is a difficult topic and one we are little prepared to understand or even notice. You can drive along Marine Drive and see the earthen levees. You can pull into Heron Golf Course and read historic markers for Vanport. You can drive out to Kelly Point Park and try to find the confluence of the Willamette and Columbia Rivers. You can wonder about a flood plain code that was placed in building code and not willing to address immediate safety concerns. There are many resources on line about the Vanport Flood for you to explore.

From the earliest time of Industrial settlement, the city and the Port of Portland have tried to remake our rivers. To turn water into land and hold back floods with walls. It works until it doesn’t. We will always ask if anyone knew the levee was going to breech in the Vanport Flood or Katrina or other countless disasters. The Columbia Corridor, as its been renamed, is known as Portland’s economic engine. It’s built on the historic Columbia Lowlands. The river is held back by earthen levees. The Columbia is connected to the Willamette and it is all a part of a vast and ancient geological system of shifting earth and water. How, after Vanport, did we learn to live within it and not against it?

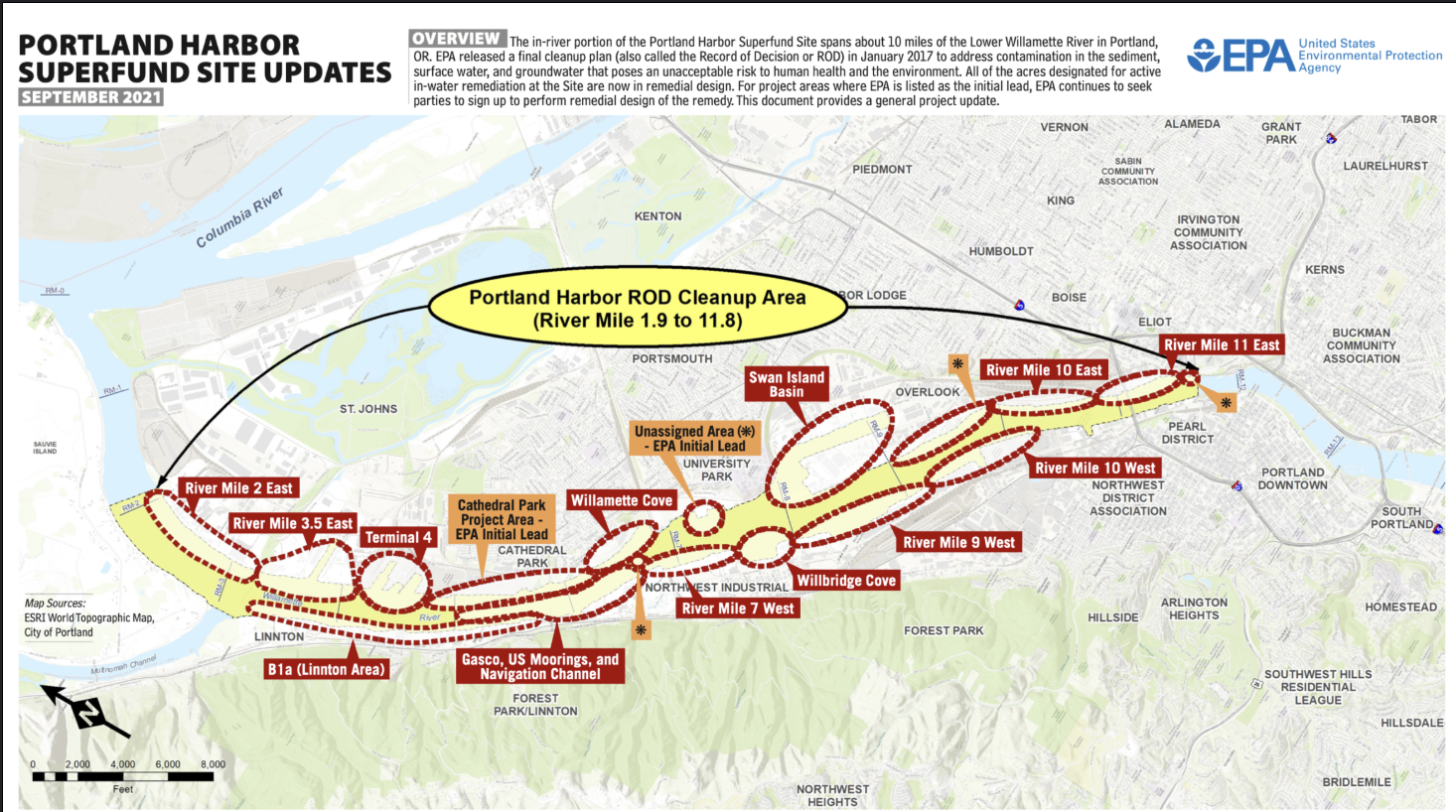

Quick Lesson #24: The Superfund Clean-Up – Economic Constraint or Opportunity

If this primer was a fairytale and the leading lady was the North Reach, what would the fairy tale be?

I imagine this when the North Reach Superfund clean-up is called a “constraint” in city documents. My mind wanders. I see our fair river as an abused and neglected lady in a tower. Nothing she does is ever good enough. The evil stepsisters of Cinderella poking and taunting. She, the Willamette River, is not the right size or shape and has too many green things hanging on her. She keeps them from going to the “Ball” and what’s with all those animals that are always singing to her. For a moment, in a meeting, this is what I see when they call the cleanup a constraint. One more thing to keep the mean sisters from getting to the elegant and exclusive “Ball.”

And then along comes the Superfund Cleanup, cutting through the thorns of Sleeping Beauty to free River from at least some of the waste that was thrown at her feet. I see the animals make their way down to her shores and sing in celebration as at least one wall is torn down. But this is not a tale of fantasy. It is the reality of the North Reach, abused and neglected and tucked away from site.

So in the world of fairytales and rivers, is the Superfund Cleanup an Evil Constraint or a Hero?

In our tale, is the removal of century old contamination a risk to the city or a tale of restoration and renewal? The largest city industries on the river, fought the designation, the design and the clean-up, for you see the Superfund Law requires the potential parties or polluters to pay for their share of the clean-up.

The Comprehensive Environmental Response, Comprehension and Liability Act (CERCLA) was created by the US congress in 1980 to create the Hazardous Substance Superfund. There are hundreds of Superfund sites across the country.

The Portland Harbor Superfund spans the North Reach from the Broadway Bridge to Sauvie Island. It includes both in water and upland clean-up. DEQ handles the upland portion and the EPA is working on the in-water portion. Although the Portland Harbor was identified as a contaminated site many years ago, the record of decision was only published in 2017. This describes the necessary remedy for the harbor.

Then each PRP (potentially responsible party) had to agree to the cleanup and begin a design. PRPs, who at first refused to sign, were fined and shortly all parties signed. Three parties have come close to finishing their design. It is now 2025. Many years have passed since the river’s contamination was documented. Why has it taken so long?

Because of the fish window, the cleanup will begin in 2026 and take over 13 years. Contractors can only work four months a year because of the fish window, but when they do, they will work night and day. Restoring endangered species habitat is an essential part of the cleanup.

Because the City of Portland and the Port of Portland are PRPs, taxpayers help pay for their portion of the cleanup. Your water bill has a superfund tax. The tribes are respected as autonomous governments and are consulted on the cleanup. The City has an obligation to make sure that treaty rights are honored and that means a cleanup that assures fish habitat.

The basics is that the contamination (industrial garbage tossed in the river) has gone deep into the sediment and that has to be either removed or capped. These chemicals cause cancer, learning disabilities, and maternal health problems. Simply put, people living near Superfund sites often have more health problems, higher levels of poverty, and have shorter lives.

There is a lot of national research on Superfund Sites. The chemicals get into the fish and if people eat them, as they did for thousands of years, they can get very sick. An important note is that the water is not necessarily contaminated. For the most part, eating fish and the riverbanks expose humans. Also different Superfund Sites present different health problems.

Knowing that the Superfund Clean-Up saves lives and prevents disability and disease, is it a constraint or heroic? Hard working people have fought for this clean-up over many decades. Endless meetings and advocacy. Steadfast, Bob Sallinger, was an early and ever -present advocate. He helped create the Portland Harbor Community Advisory Group which, after 25 years, still provides monthly meetings to educate the community. Many other river groups embed superfund education in their work; the River Keepers, PHCC, the Mosquito Fleet and more. The superfund sites spread out from the Broadway Bridge to Multnomah Channel. The Columbia River and the Slough also have superfund sites and clean-ups.

The EPA’s Portland Harbor Superfund website is full of information. The fact sheets are available in multiple languages. Both DEQ and EPA staff are incredibly caring environmental advocates who grew up wanting to help the world. The thoughtful process of community engagement has been an inspiration.

The Portland Harbor Superfund Cleanup will cost billions of dollars. Millions of tons of contaminated soil will have to be removed. Given that, one wonders why city policies do not do everything possible to prevent future contamination? As long as they see it as a constraint and not as an important lesson in managing the North Reach, an important possibility for a change in policy is lost.

Is the Portland Harbor Superfund Cleanup a constraint to economic activity or is the health and safety of our communities the most basic building block of a thriving city?

Quick Lesson #25: Can any of the CEI Hub tanks along the North Reach ever be taken down?

Driving along Highway 30, this seems impossible. Miles of steel for as far as you can see. An economy built on government sanctioned land grabs, railroads, and powerful oil companies. But the North Reach is a land that was built on the impossibles. The great glaciers melting and carving out the Columbia and Willamette Rivers and leaving behind an ecological wonder of impossibly perfect design. We look for the impossible beyond this geological event and the moments of human effort, both destructive and healing.

When Immigrants first came to the North Reach, they were often employed to cut down whole forests of huge old growth Douglas firs. They did this with hand saws after somehow getting across oceans and continents to land that would become Portland. They climbed huge trees, somehow got them down logging roads to the river, and built mills and towns. Then they did it all over again when the forest grew back, and then with a new determination Forest Park was created and the forest was allowed to grow again and this time forever. Stubble and fallen logs turned into a park. Believing in the impossible.

When World War II gave birth to genocide and destruction, the people of the North Reach built two Liberty Ships every three days for months. One whole ship. They came from all over the country and built 600 ships. After the war, they took them apart again. Ships, as big as many of the CEI Hub tanks, were built in one day and taken apart again. The impossible.

The former Willamette Cove and McCormick and Baxter sites were left with skeletons of cement factories and decaying, forgotten docks. Poisonous chemicals sunk into the river and land where they stood. Now, after decades, the old factories are gone and the work is well under way towards recovery and restoration. Portlanders can do hard things. The Impossible.

The salmon have returned to the Klamath River after taking down the dams. The impossible made possible.

I believe the CEI Hub tanks will come down one day. Steel is strong, but it also rusts and decays. The oil companies may paint over the rust so we can’t see it, but like an old car left in a pile of blackberries, metal does decay. They are not forever metals or forever CEI Hub tanks.

A few of the cities that took down their waterfront tanks include: Norwalk, Connecticut; Brooklyn,Burlington, Vermont; Camden New Jersey and South Portland, Maine. Once these cities came to believe that a tankless waterfront was better for their city’s economy and well-being, the solution followed an engineering formula. Commitment was the hard first step.

Once a city makes this commitment, they followed these steps: decommission, drain remaining oil, clean, fill with some form of slurry or cement, cut off the pipelines, take them down, recycle the metal. Last, but most difficult and expensive, is to clean the area and make it available for future use. There are companies that specialize in this.

In the Portland Harbor, there are 630 tanks and the ones that are not in use, have not been officially decommissioned. Despite the fact that there are numerous safety codes that prohibit aging, rusting, derelict structures, they remain. At this time, only 415 are listed as active. I wonder why, when Oregon’s population was far, far less than it is now, why they built so many and why they made them as big as they are. How can we have so many listed as inactive with a much greater population? Remember the Olympic Pipeline was not made until the 1960s.

I try to go back in time, when the tanks were not there, to understand how they might begin the process of removal. The 1930s was a time of extremes in our nation. The Gilded Age and the depression, the rise of big oil and railroads, and the first World War. Portland politicians had worked hard to make Portland (and not more likely sites) Oregon’s official “deep seaport.” Never mind that it was a hundred miles from the sea and the river was 12 feet deep in many places. The Gilded Industrialists did the impossible on the Oregon frontier. They made the braided river into a deep seaport. They built huge navy ships. They also built gas and oil tanks. They riveted them together much like the ships. It is probable that railroad land was used in many cases. Coal was the earliest source of gas and was manufactured in Portland. Oil was shipped in via train and barge. This pattern was repeated all over the United States.

Is taking down Portland’s unused aging, rusted tanks possible? We are a state that built huge dams. We are city that built thousands of houses during World War II, destroyed them, and then asked tax payers to pay for more a few decades later. The city and state tore down whole towns and neighborhoods to build highways. They built a highway on the downtown riverfront and then a few decades later tore it down to make a park. They know how to do the impossible.”

Want to learn more? Watch Jay Wilson’s CEI Hub flyover on u-tube to see the condition of the tanks. Research CEI Hub vulnerability studies on line – city, state and county. Take a drive out highway 30. Drive down Front Avenue off of the Kittridge Bridge or in Linnton. Walk along the river in Cathedral Park.

Quick Lesson #26: Ferries, Docks, and Water Access in the North Reach

What does it mean to be a river community built on the last ebb and tide of the Willamette River? To live within its rhythms and move upon the water? To safely swim, canoe, kayak, and take a ferry to the next community up and down the river? What does it mean to be a city connected to the river?

Long before the docks and ferries and before the large ships and barges, indigenous communities designed and built canoes for travel on the river. Different canoes had different purposes. They were the means of travel since time immemorial.